A new anthology of adventures for 5e D&D offers tables the chance to pull of fantastical heists, but Keys from the Golden Vault stumbles from step one and never gives readers enough tools to pull off its premise.

TL;DR – Worth a buy?

This review took me several weeks of daily effort to cobble together for a variety of reasons, but primary among them is: the book disappointed me deeply.

Despite several cool NPCs and quirky magic items, the book doesn’t do enough to merit your attention: I’d skip it.

Why, tho?

5e doesn’t have the mechanics to handle heists well, and the book baffflingly provides no new frameworks, mechanics, or development to help GMs run such stories. Several entries of the anthology are heists in name only, even if they’re fun adventures on their own.

Book Overview

Keys from the Golden Vault is a heist anthology for Dungeons and Dragons 5th edition. In its marketing material, there are clear connections drawn to popular heist media like Ocean’s Eleven, Mission Impossible, and more – the titular Golden Vault, a collection of beneficent and magnanimous thieves, even send their missions to the party through magical music boxes powered by magical keys that self-destruct after they give details about the job.

The first chapter “A Collection of Heists” lays out the fundamentals for how the book and anthology of heists operates: mission briefing, planning, execution, conclusion. It then delves into the 2 things I hear the book applauded for the most: The Golden Vault and Rival Crews.

The Golden Vault

The golden vault summary is about 1 page in length and describes a beneficent group of thieves who steal from the malicious at the request of the downtrodden or slighted. The group has 3 details:

- Meera Raheer, who is the party’s handler, is a human commoner whose backstory shows her family was framed by an evil mayor. She chose to work for the golden vault after they helped clear her family’s name.

- The golden vault sends magical keys that when put inside magical lock boxes play a pre-recorded message about a job, hand-picked by the golden vault.

- The golden vault abjures violence and does not support or condone bloodshed in any but the most extreme cases (to prevent “kill everyone, take the thing” from being the answer to all heists).

Rival Crews (One of two Heist Complications)

The rival crews section begins on the last 10th of page 7 and gives a list of 6 potential members of a crew that might find themselves after the same payday as the party. Each of the 6 are given an alignment and a trait (such as loving puns) and a chart offers them a different NPC statistic at each tier of play (for example, Enna can be a bandit for levels 1-4, a spy for levels 5-8, and an assassin at levels 9-11). On page 9, there is a chart for motivations for the rival crew, giving them a reason for being on the job – no reason is tailored to the job specifically, but in general they work.

The Problem Child – “The Moving MacGuffin”

Sticking out of the extremely short chapter like a blood blister seeping pink liquid, the moving macguffin section, with is 4 paragraphs long, speaks directly the DM and tells them to complicate a heist, move the party’s objective before they get there.

The premise is fine, but I stand in complete contempt that the veil of the fantastical and reverent is peeled off as to call each of the plot devices used in the heists a “MacGuffin.” Imagine opening Curse of Strahd or Storm King’s Thunder and reading about “Finding the ancient MacGuffins” in chapter 1 and chapter 3, respectively. That level of irreverence and unflavored hand-waving left an extremely sour taste in my mouth even before the very first adventure. I didn’t know, at the time, it’d the shadow of things to come in terms of the book’s production level and design.

The Anthology

Listen, I’m not going to do a deep dive into every single heist in this book, as it would take almost as long as the book took to write. Instead, here are the details that stood out the most too me when digesting the book as a whole. I know these might sound overly negative, but “standing out” in a book review isn’t wearing a red dress in a sea of black ones, it’s a splinter waiting to snag a passing finger. We’ll talk about “What Works” later on – a critical sandwich.

High Magic

This anthology is shockingly high-magic. Museums have tens of thousands of gold worth of magical lighting (continual flame is 140gp each, btw), scrying mirrors on most walls, enchanted pass-cards that bypass permanent alarm spells, awakened statues, rugs, swords, dolls – the level of magic in each location is tantamount to any other location in 5e official releases I have ever read. Spelljammer uses fewer magical devices.

The big problem with the magical systems the party has to bypass on these jobs is… they’re don’t seem all that clever to me or interesting, they’re just real-life security systems made magical for convenience’s sake. Magical scrying mirrors = surveillance cameras. A flying train = a plane. Pass keys = … well, pass keys. Animated suits of armor = a person with a taser paid to stand there.

Other high-magic occurrences stand out as gargantuan investments, too, like nearly a half-mile of antimagic field prison cells, an army of automatons controlled by a cyborg gnome, magical crystal gem tattoos that make holographic 2-dimensional maps, or a magical train that lays its own tracks while flying through the multiverse. I promise I’m not making any of this up.

What having such powerful magic in these adventures does is undercut the non-magical barriers the party might have to bypass. While navigating the scrying-mirror studded room of alarm spells with animated suits of armor triggered by invisible alarm spells… the party might have to get out of a DC 10 net trap? While passing the arcane lock barricaded rooms of the isolated ice prison of antimagic cells which has an alien spectator guarding its armory, the party may need to open a locked desk with a DC 12 check?

If you enjoy high fantasy, high magic, common magic, and magic-as-technology, you might get a fair amount of inspiration from this book, but those who want to play the muscle who threatens a guard to keep quiet or break open a door with a prybar, you’re going to be disappointed. Likewise, most magic is used to simulate modern day technology, where a magical barrier that causes all sound to be amplified out to a distance of 300 feet (not in the book, i made it up) is far more interesting BUT also far more difficult to run.

Maps ~are~ the Planning

A huge amount of the ‘planning’ stage of each adventure is given in the map. Two versions are supplied: one for the players (usually hand-drawn with little notes from whoever scouted the location before the party) and one for the DM with far more detail and exacting layouts.

I gotta say, I actually LOVE the maps in this book. The hand drawn versions are honest and fun, not quite right, but close enough, and seem like they’d be a divisive talking point for a party, which is always fun. The layouts make sense and are sensible (even if the inordinate amount of magical stuff seems mind boggling to me), and handing the party a variably trustworthy map up-front is a wise decision.

However, there’s usually very little consideration for the planning stage of each heist BEYOND the map and whatever information is detailed on it. Some of these locations are so large and well-fortified that drawing circles of “flesh eating death beetle pit” on the floor is usually all that’s on offer. Having an entire session (or multiple sessions) of D&D in which the party attend a gala and chat with employees, look for ventilation, measure out rooms, watch rotating shifts of guards, etc could be fun, but in general looking at the map and hearing a description of the thing, if the party can arrive at the location, is what’s on offer.

What’s more, in the vast majority of these adventures, the party is GIVEN a way into the locations by the NPC that’s requesting the job (or the Golden Vault itself). For instance, the party is already on the invite list to the gala. The party is GIVEN identities as guards or cooks that grant them access to the prison of Revel’s end. Etc etc etc.

With information gathering already done and a means to enter the place already handled, there’s not much else for the party to plan. Who goes where and what they wanna do if XYZ happens isn’t the most graceful part of the planning process, and many find it frustrating (It’s why Blades in the Dark quite literally designed it out of their heist-based TTRPG system).

A Shift in Tone

[Hello again from three weeks after starting this review… If you feel a change in tone for this review, that’s why!] Keys from the Golden Vault has a peculiar habit of introducing vernacular that just doesn’t fit in a traditional fantasy sense but would work in a science fiction high-fantasy sourcebook. Some that stand out are “hang out” “chat” “pseudoscience” and others. What this does is makes the hard-baked fantasy elements of devils and demons or magical constructs feel contrasted by modern day descriptions: monitors on the room of a security office, hallway waiting areas, ‘fake news’ reactions to scientists warning of impending doom. I’m not sure where the reaction comes from, but reading through the book, they stuck out like unexpectedly hard bits of food during a meal and left me so wrapped up in figuring out what they were doing that I couldn’t focus on the otherwise useful or fun details of some locations.

Overall

I hope you pardon me for the lateness of this review. Finishing Keys was a mercilessly difficult task for me for a variety of reasons, ranging from existential crisis brought by the unimaginable shift in the D&D community to covid scares and unexpected project deadlines.

I feel horrible for all the people who put their blood, sweat, and tears into this book – waited for months and months to see it brought to fruition, were so proud to have their chance to be in the spotlight for an official product! I can imagine how exciting that must have been and my heart and best wishes go out to every freelancer and all the signed talent. Bad reviews, even from as fringe a source as me, sting, but this book feels underdeveloped in every regard. It feels slapdash in many areas and like a pile of ideas were 3-hole punched and snapped into a zip-up binder for everyone to look at more than a cohesive well-crafted book.

The strange CGI art prompt pieces that made it into the full release, the strange verbiage shifts mid-encounter, the oddly pejorative way of describing plot devices, the use of magic as a 1:1 with modern technology – all of it felt lacking in the attention to detail and inspiration these anthologies try to cultivate.

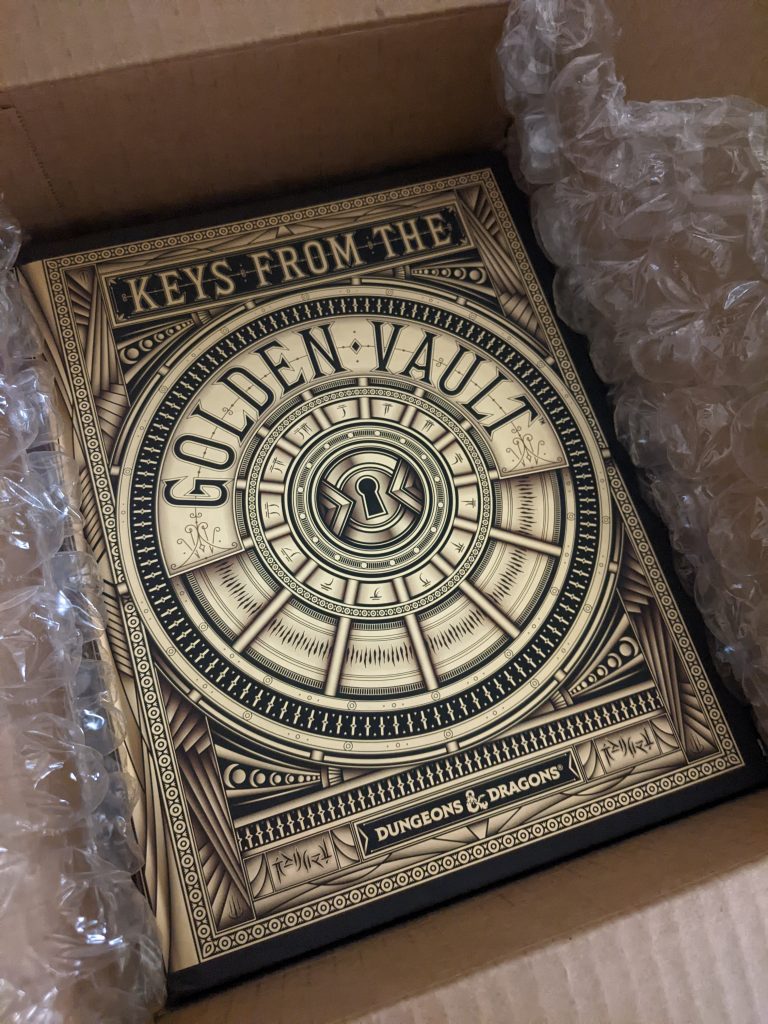

According to the community feedback and my own personal experiences, this book hasn’t went over well and falls into the same trap my previous review of the Ravenloft source book did – it doesn’t give DMs new tools or a cohesive narrative to offer their players. It doesn’t even address simple problems like how Druids largely bypass all forms of heist setbacks by level 3 with their obscenely useful Wildshape. There’s just…. not enough here to slake most peoples’ thirst, even if the special edition cover is magnificent. The D&D heist curse continues.

I don’t always advocate rolling, but when I do… be sure you have to Drop the Die.

Review by JB Little, Follow me on twitter for more “useful” information.